“Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.” — Albert Einstein

Curiosity is a basic characteristic of scientists in many fields. The ability to observe and form hypotheses to verify or refute is a foundation of the scientific method. Edward Jenner, an English physician and scientist in the late 1700s, pioneered smallpox vaccination by using lesions from workers who milked cows with cowpox, a less virulent form of pox that rendered them immune to smallpox. His understanding of the natural world inspired him to create an effective way to block the scourge of his country and a global threat. Edward Jenner and those like him sought knowledge by embracing the animal-human interface. Today, our scientists are continuing in the footsteps of Edward Jenner. By seeking answers to complex biological questions in nature, these modern-day pioneers are providing fundamental knowledge to advance the health of animals, people, and our planet.

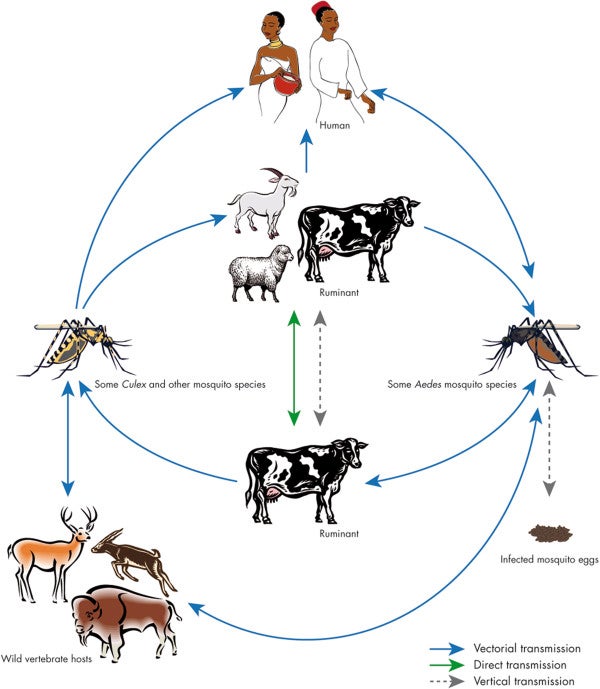

Cycle of Rift Valley fever. (From “Towards a better understanding of Rift Valley fever epidemiology in the south-west of the Indian Ocean” – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate.)

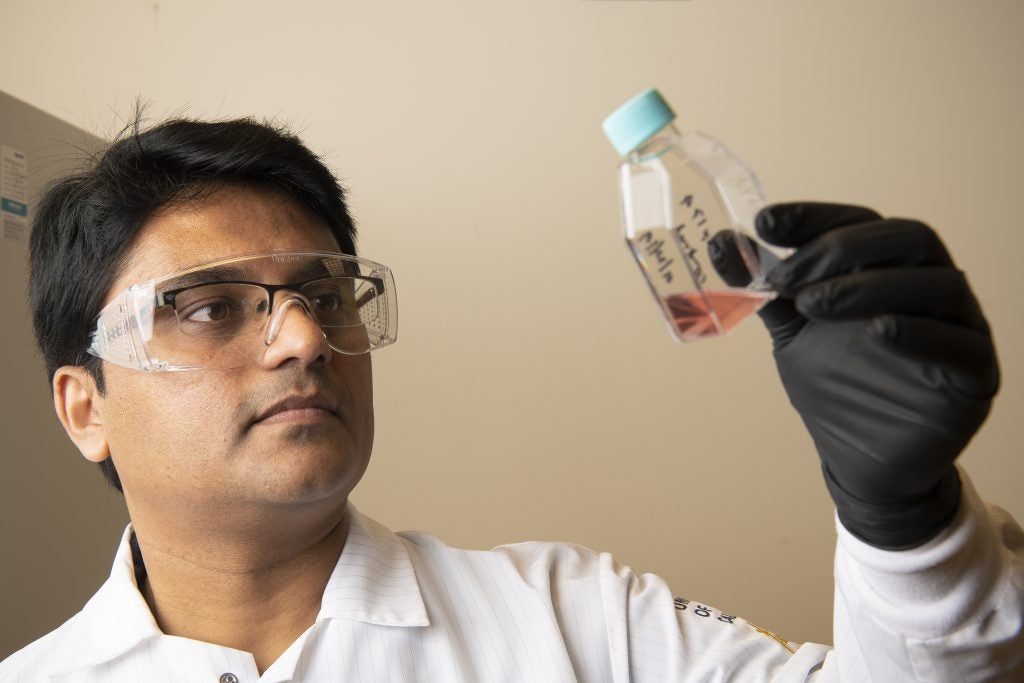

This week, CEPI—the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations—announced an initiative to create a human vaccine for Rift Valley Fever (RVF) virus. The virus causes an acute, febrile disease most commonly observed in domesticated animals (such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, and camels), with the ability to infect and cause illness in humans. The majority of human infections result from contact with the blood or organs of infected animals or from the bites of infected mosquitoes. Vaccines against RVF have been effective in livestock, and one of these vaccines, DDVax, will be the basis of the human vaccine candidate. DDVax was developed at the Centers for Disease Control by a team including Dr. Brian Bird, now of UC Davis.

This is a continuation of disease innovations involving our scientists. For instance, Dr. Tracey Goldstein from our One Health Institute and her colleagues used careful data collection, modern methods of virus detection, and well-designed field studies to discover new strains of the Ebola virus and shed light on animal reservoirs of this modern-day threat to global health. They tracked down this killer virus in common bats in regions of Africa that have suffered devastating epidemics of Ebola infection. In another example, Dr. Christine Kreuder Johnson and her research team published models based on massive data sets that predict wildlife reservoirs and global vulnerability to deadly vector-borne viruses that infect both animals and humans. Dr. Patty Pesavento, in our Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, has devoted her research to analyzing novel patterns of disease in wildlife and identifying causal agents. Her research, like that of Jenner, relies upon keen observation of natural disease; in her case, to discover novel viruses in species ranging from cats to raccoons. Her investigations have led to unique insights into the cellular interactions of these viruses and into the origins of cancer and inflammatory diseases relevant to animals and people.

This is a continuation of disease innovations involving our scientists. For instance, Dr. Tracey Goldstein from our One Health Institute and her colleagues used careful data collection, modern methods of virus detection, and well-designed field studies to discover new strains of the Ebola virus and shed light on animal reservoirs of this modern-day threat to global health. They tracked down this killer virus in common bats in regions of Africa that have suffered devastating epidemics of Ebola infection. In another example, Dr. Christine Kreuder Johnson and her research team published models based on massive data sets that predict wildlife reservoirs and global vulnerability to deadly vector-borne viruses that infect both animals and humans. Dr. Patty Pesavento, in our Department of Pathology, Microbiology, and Immunology, has devoted her research to analyzing novel patterns of disease in wildlife and identifying causal agents. Her research, like that of Jenner, relies upon keen observation of natural disease; in her case, to discover novel viruses in species ranging from cats to raccoons. Her investigations have led to unique insights into the cellular interactions of these viruses and into the origins of cancer and inflammatory diseases relevant to animals and people.

This past year, our veterinary scientists provided new and fundamental insights into topics covering a full range of disciplines from nutrition to ophthalmology. For instance, Dr. Joshua Stern has brought attention to the link between legume-based diets and cardiomyopathy in certain breeds of dogs. The Food and Drug Administration subsequently announced the investigation of 16 pet food brands linked to the disorder. Dr. Stern’s insight required keen observations of his patients referred to our cardiology service in our veterinary hospital. Similarly, Dr. Danika Bannasch, a geneticist in our Department of Population Health and Reproduction, used modern genetic methods for her insightful studies of natural disorders in dogs. Her role in transforming canine health earned her global recognition through an International Canine Health Award. Our oncology researchers are actively pursuing therapies to combat canine cancer, while at the same time producing important data to inform human cancer investigations. This past year, Dr. Jenna Burton led an extensive network of researchers in a phase I study for lymphoma-bearing dogs to evaluate differential efficacy, toxicity and pharmacokinetics of novel compounds that have implications to expand human and canine cancer therapeutic options.

This past year, our veterinary scientists provided new and fundamental insights into topics covering a full range of disciplines from nutrition to ophthalmology. For instance, Dr. Joshua Stern has brought attention to the link between legume-based diets and cardiomyopathy in certain breeds of dogs. The Food and Drug Administration subsequently announced the investigation of 16 pet food brands linked to the disorder. Dr. Stern’s insight required keen observations of his patients referred to our cardiology service in our veterinary hospital. Similarly, Dr. Danika Bannasch, a geneticist in our Department of Population Health and Reproduction, used modern genetic methods for her insightful studies of natural disorders in dogs. Her role in transforming canine health earned her global recognition through an International Canine Health Award. Our oncology researchers are actively pursuing therapies to combat canine cancer, while at the same time producing important data to inform human cancer investigations. This past year, Dr. Jenna Burton led an extensive network of researchers in a phase I study for lymphoma-bearing dogs to evaluate differential efficacy, toxicity and pharmacokinetics of novel compounds that have implications to expand human and canine cancer therapeutic options.

These examples indicate that our scientists today are following the footsteps of earlier pioneers, armed with modern powerful tools at their disposal. Even with these tools, at the heart they are continuing the essential traditions of observing the natural world, questioning how life works, and testing their hypotheses to produce hope for the future.