“Learn from yesterday, live for today, hope for tomorrow. The important thing is not to stop questioning.” — Albert Einstein

Curiosity is a basic characteristic of scientists in many fields. The ability to observe and form hypotheses to verify or refute is a foundation of the scientific method. Edward Jenner, an English physician and scientist in the late 1700s, pioneered smallpox vaccination by using lesions from workers who milked cows with cowpox, a less virulent form of pox that rendered them immune to smallpox. His understanding of the natural world inspired him to create an effective way to block the scourge of his country and a global threat. Edward Jenner and those like him sought knowledge by embracing the animal-human interface. Today, our scientists are continuing in the footsteps of Edward Jenner. By seeking answers to complex biological questions in nature, these modern-day pioneers are providing fundamental knowledge to advance the health of animals, people, and our planet.

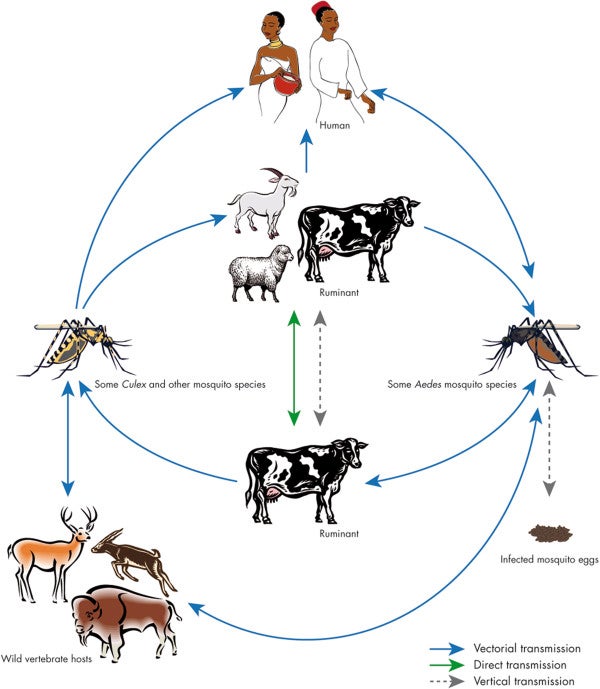

Cycle of Rift Valley fever. (From “Towards a better understanding of Rift Valley fever epidemiology in the south-west of the Indian Ocean” – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate.)

This week, CEPI—the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations—announced an initiative to create a human vaccine for Rift Valley Fever (RVF) virus. The virus causes an acute, febrile disease most commonly observed in domesticated animals (such as cattle, buffalo, sheep, goats, and camels), with the ability to infect and cause illness in humans. The majority of human infections result from contact with the blood or organs of infected animals or from the bites of infected mosquitoes. Vaccines against RVF have been effective in livestock, and one of these vaccines, DDVax, will be the basis of the human vaccine candidate. DDVax was developed at the Centers for Disease Control by a team including Dr. Brian Bird, now of UC Davis.